on suicide, gratitude and compassion

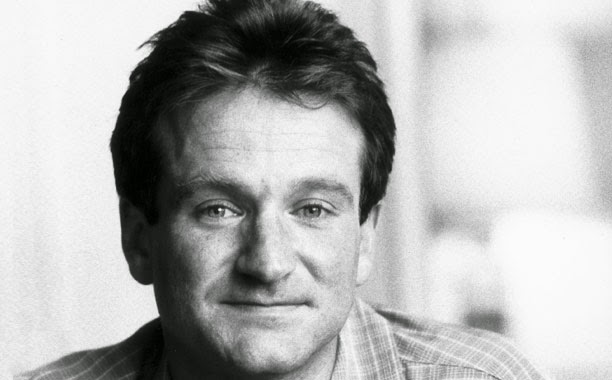

The past few weeks have brought headlines that ask us to grapple with our deepest hurts and fears. Among them was news of the death of Robin Williams.

Christians can be clumsy when it comes to deciphering mental health issues. A thousand voices rushed to weigh in on the selfishness of suicide. Some mused on how a death like Williams’ illustrated the emptiness of life apart from a relationship with God. Those who expressed sorrow over his death were scolded for their blind adoration of celebrity, and even called racist or provincial for grieving a headline less grievous than others that vied for our emotional capacity last week.

But I openly admit that it hit me hard.

Maybe that’s because my former pastor (the one whose message led my son to Christ) put a gun to his head.

Maybe that’s because I helped my dear friend clean out the apartment where his father answered hopelessness with finality.

Maybe it’s because depression and mental illness know my family.

The sentiment that best captured the way I felt about Williams’ death (and the response of others to it) was expressed by my cousin Amy on Facebook. She said simply:

“For those of you who judge suicide, feel grateful.”

Yes, grateful. Because if you are able to sit comfortably in judgment on it you cannot have sat next to its casket and recognized its face as that of someone you loved. Only someone able to hold suicide at arm’s length could write and post some of the things that were written this past week. We are so quick to process tragedy out loud and online. I wonder if a few decades from now we will have learned a more measured approach to broadcasting our thoughts.

Those who know suicide also feel grateful, though for different reasons. We feel grateful for the time we had and for the memories we hold. We feel grateful for the irreplaceable contributions those we have lost made to our lives and to the world. And we feel grateful for the solace of shared understanding among the community of those who know that suicide is not simple, that it invalidates neither the gift of a person’s life nor the love we felt for them.

We buried Amy’s brother, my cousin, in the frozen ground of February. He was not a coward. He was not selfish. He was brave and giving, brash, bright and beloved. He was a gift.

At the very least, anyone who has ever known the lightness of heart a Robin Williams monologue could infuse ought to find room to grieve his loss. If laughter is the best medicine, Robin Williams was an exceptional doctor. As with all the best medicines, we learned to our sorrow that the cost was dear. If you choose to judge him, please have the courage of your convictions never to laugh again at another of his brilliant contributions. We have all laughed at his expense, whether we knew it or not.

So forgive me if I mourn him. I cannot keep his story at arm’s length, and my guess is that many people you know cannot either. They have been fighting for their breath this week, avoiding the evening news, quietly coaching themselves to do the next thing and to cling to whatever healing they have found. So if you don’t know suicide as they do, be grateful. And let your gratitude prompt you to pray for the comfort of those who mourn. Those are words which we can never speak too hastily, and which we will never have cause to regret.